Zoe Hinton, Lecturer on MSc International Fashion Management, Fashion Business School, London College of Fashion

It is becoming increasingly apparent that technology is ‘rewiring students’ brains’ (Briggs, 2014) and educators increasingly find mobile devices ‘impossible to ignore’ (Gerson, 2015). With the premise that the more time students spend as active participants in learning activities, the more they learn, this article considers how mobile phones can be used to benefit ‘digital native’ (Levy, 2014) students in the classroom. It explores the need to harness mobile technology as well as the distraction that these devices cause. In this new world of constant connectivity it is critical to engage students and integrate mobile phone use into the lesson plan, fully exploiting the technology to hand (Herlong, 2015).

mobile phone; active learning; technology; classroom; digital

In universities today, student bodies are largely made up of cohorts of what has come to be termed ‘digital natives’ (Levy, 2014) or ‘Generation Y’, who have grown up with mobile technologies constantly to hand. How to deal with this is a source of constant debate between teaching staff, keen to address the impact of the ever-present mobile phone and its position within the classroom. Some believe that we need to adapt to this new way of learning by harnessing mobile technology (Barret, 2012), whilst others are acutely aware of the distraction that these devices cause and the negative impacts they can have on productivity (Beland and Murphy, 2016). According to Briggs (2014) it is becoming increasingly apparent that technology is ‘rewiring students brains’, as such, educators increasingly find mobile devices ‘impossible to ignore’ (Gerson, 2015).

Despite various opposing opinions on the subject, many educators remain of the view that ‘Generation Y’ are adaptable to the technologies that surround them and highlight the potential opportunities of integrating digital platforms within the learning experience (Honore and Schofield, 2009). Teaching always attempts to focus student behaviour and learning is often reliant on external sources to do so, with interactive technologies being no exception. A familiar conversation amongst educators centres on the fact that students are continuously glancing at their mobile devices during lectures. In a study by the University of Haifa (2012), almost all students admitted to accessing social media via their mobile devices during lesson time.

To manage this, teaching staff within the Fashion Business School at London College of Fashion are already beginning to integrate mobile use into lecture delivery, using various platforms to fully engage our often large cohorts of students. A term long study, run by a lecturing staff member, was undertaken to explore the benefits and challenges of using mobile phones and interactive technology within the classroom. Various perspectives were sought, not only from the students (year 2 MSc Fashion Management), but also from teaching staff working at different levels of education. In addition, the study captured the perspectives of two people working in the fashion industry in order to identify the ways in which mobile technologies could be used, not only to engage students, but also to effectively and appropriately prepare them for the workplace.

The perspectives sought from teaching staff were gleaned via an online survey of those teaching at primary, secondary, further and higher education level, where responses highlighted both the positive and negative impact of mobile phones. Just over half of those surveyed claimed they were a ‘distraction’ and a ‘nightmare’ whilst the remaining half viewed them as a ‘helpful’ tool which ‘enhanced the teaching and learning experience’. Such split attitudes were reiterated by two follow-on lecturer interviews. When asked about the mobile phone integration strategies, participants felt that they had been a ‘useful tool’ due to the ‘instant reward’ they provided, but they also struggled to manage their use due to their ‘disruptive’ effect, with negative impact on student engagement. This was also explored with student viewpoints via a focus group (of 4 students). It was interesting and perhaps surprising, to learn that the students perceived mobile phone use as a ‘distraction’, as they found the ‘instant response’ that it provided difficult to ignore.

In order to understand the current generations ’anytime, anyplace, anywhere’ communication culture, and its impact on the teaching world (Childalert, 2017), it became necessary to explore mobile phone use not only at FE and HE level, but also within secondary and even primary education. Staggering statistics emerge from various data sources. Nearly one third of primary age children now own a mobile phone, and 20% of young peoples’ media consumption occurs via mobile devices (Rideout et al, 2010). Statistics reveal challenges faced by teaching staff, right from these early years, when both parents and pupils are increasingly expecting a digital presence in their education, be it via interactive smartboards or through basic computer access. Within secondary education, the impact of mobile phone use gains momentum, with 85% of 15 to 18 year olds owning a device (Rideout et al, 2010, p.10). In response to their subsequent impact on student learning, there is evidence that some secondary institutions are banning mobile phones in order to reduce such distraction and refocus students’ attention. Beland and Murphy (2016) observe that this has a positive impact, reporting that student performance (in exams) after mobile phone bans has significantly increased. Often, those that do allow mobile phones, do so under strict guidelines and with careful handling, ensuring complete autonomy of their mobile phone policies and effectively managing any distraction (Beland and Murphy, 2016).

In terms of evaluating mobile phone use at Higher Education level, it became clear that investigating the student perspective about mobile phone use in the classroom was critical. The subsequent focus group generated interesting views on the subject. The students questioned were certainly of the view that their mobile phone was indeed a distraction, stating that they tried to keep their phone ‘out of sight’ to minimise any negative impact. However, it was still evident that in some cases they nonetheless found them impossible to ignore and so intentionally used them in lesson time. This became even more complex when considering the integration of text alerts linked to user profiles and therefore visible on laptops, ensuring that even when mobile phones were removed, the issue remained due to the inevitable use of these other digital devices in the classroom. The students’ viewpoint on the reason for using mobiles during class, also raised interesting issues, with students stating that their use of their mobile would depend on ‘how exciting the lecturer was’. Participants expressed significant frustration with teaching staff, highlighting how lecturers occasionally were visible using their own phones in lectures given by others, reinforcing the points made by Gerson that it is necessary to ‘lead by example’ in order to demonstrate the use of mobile phones as a useful tool rather than a distraction (2015).

When reviewing the interviews with academics at UAL, it also became clear that not only the students but also the teaching staff were demonstrating a very similar viewpoint, and further validating the notion that current student population as an ‘easily distracted generation with short attention spans’ (Purcell et al., 2012). When questioned, teaching staff appeared unsure of their position on mobile phone usage, with ‘mixed feelings’ on how to integrate such devices into the lesson plan effectively. They were clear that their students were all in possession of mobile phones so therefore they ‘may as well’ be integrated into the lesson plan, and were also of the opinion that students really enjoyed such integration. However, still highlighting the devices as a disruption, the question of their use undermining the innate need for deep learning remained. It was therefore clear that these academics found them difficult to ignore (Gerson, 2015) but equally challenging to manage due to the impact of the current ‘attention deficit world’. Faced with this current and inevitable trend for multitasking teaching staff were all too aware of the challenges mobile devices bring (in relation to concentration) and the ability to bring students together, creating situations of shared learning. It became clear that staff required more direction on how best to use them and explore their potential in the classroom (Hardison, 2013), in harnessing the technology to create an ‘engaged and individualised educational experience’ (Levy, 2014).

Two lecture scenarios were devised, whereby the first – hereafter referred to as the ‘control’ lecture – was run without digital intervention and the second integrated mobile phone into the lesson plan. These lectures were delivered within the same unit of teaching, to the same cohort of students, with very similar subject matter. It was critical to ensure that lecture delivery without mobile integration used other methods of engagement, drawing on the work of Bligh, who highlights the importance of discussion and other variations in auditory stimulation and the use of visuals to ‘arouse’ interest and ‘motivate’ the receiver (1998, p.50). This control lecture included discussion points (a method outlined by Hayes et al., 2012), deploying videos and relevant imagery at strategic times to ensure maximum engagement. These strategic points allowed students several minutes to discuss a given subject, which effectively restored attention and motivated them for a further 15 minutes, wherein the next strategic activity took place. This followed Bligh’s research findings that suggested using a variety of teaching methods increase heart rates and therefore encourage greater interest at critical points in the lecture (1998).

In contrast the ‘digital’ lecture contained ‘multimedia rich’ content (Baturay and Bay, 2010). This lecture’s approach sustained attention by using strategic discussion points that also incorporated a test in which students participated via an app on their device.

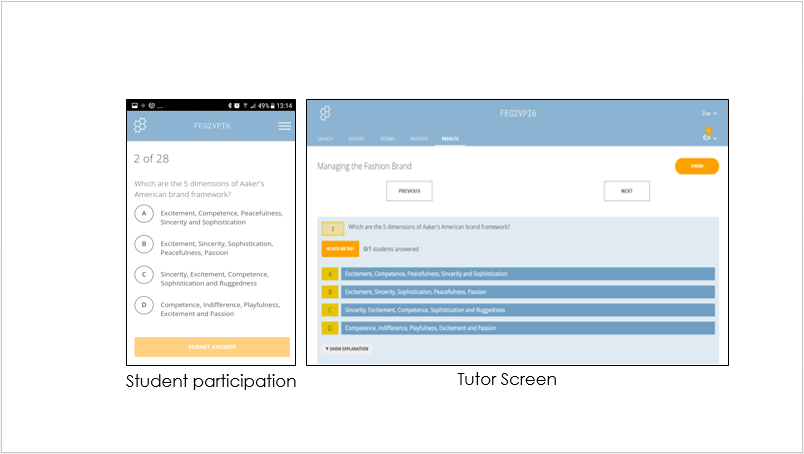

This was delivered using the mobile platform ‘Socrative’, which enabled students to easily participate and teachers to manage online via the teaching screen (Figure 1). Students were surveyed after both scenarios and the results were analysed to ascertain whether integration of mobile devices acted as a tool to improve student engagement.

Feedback from lecturer interviews when considered in relation to relevant literature, indicates that the use of mobile phones as teaching aids should be explored more extensively. Lecturers discussed the use of several additional platforms, including Facebook and Poll Everywhere, which they felt could be of potential benefit. This reiterates studies that have highlighted mobile devices as a ‘powerful tool’ for improving engagement (Levy, 2014). However studies by others, such as Bligh, conversely point out that ‘dazzling presentations do not necessarily result in learning’ (1998, p.100). Reviewing these two opinions indicates that using mobile devices effectively to maximum effect would require seamless combination of both digital and non-digital methods as a way of ensuring maximum engagement. Merging physical and digital worlds in this way (Bailey, 2015) could be as successful in teaching as it has been in the retail environment, for which the Fashion Business School prepares its students. In response, several other platforms were incorporated into lecture delivery, alongside more traditional teaching methods throughout the same term, with positive results as indicated by student feedback gathered in the termly unit evaluation survey.

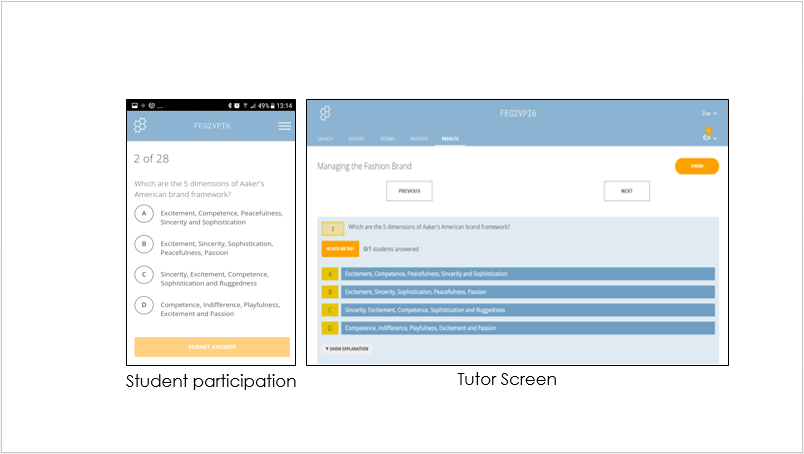

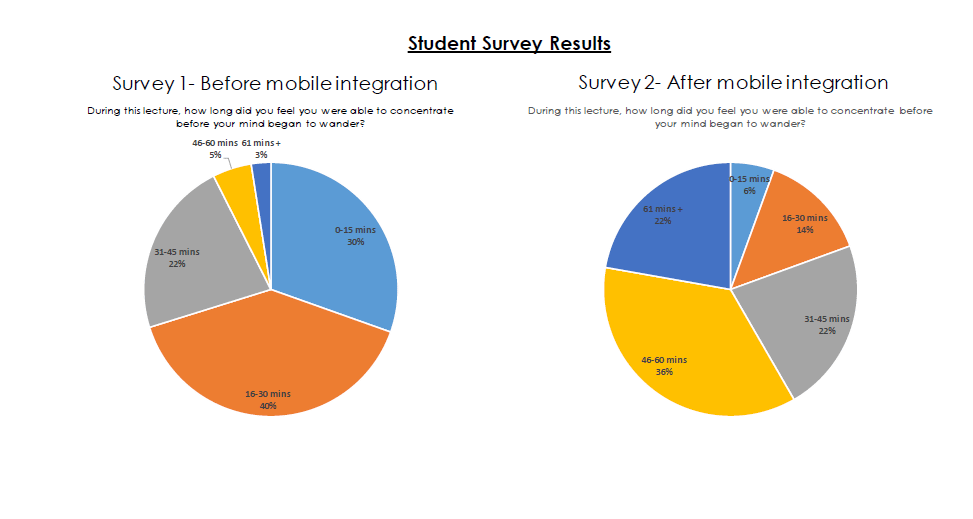

The results of the surveys following both the ‘control’ and ‘digital’ lectures were enlightening, and worked to answer questions as well as pose new ones for further research. Initially the concept of concentration was addressed, with the feedback demonstrating that students felt that they concentrated for longer when mobiles were fully integrated into the lecture. Of the 40 students questioned, 80% stated that they felt they concentrated for 30 minutes or longer when mobile integration was included in delivery; compared to 30% of students in the non-mobile lecture (see Figure 2). This could indicate that student concentration indeed was improved by harnessing mobile technology within the lesson plan, but paradoxically, when asked how often they looked at their device during the lecture (for anything that was not directed by the lecturer), the results did not change to a significant extent (Figure 3). It is interesting to note that, even though they looked at them a similar number of times in both lectures, students in the digital lecture were not viewing their devices as a distraction and felt they were able to concentrate for longer. It became apparent that students (perhaps subconsciously) do not view mobile devices as a tool that detracts attention, which contrasts with student focus group comments. After reviewing the work of Barrett (2012), it became clear that teaching staff and academics need to fully adapt to the ways in which this new generation perceive these technologies in order to fully engage the cohort. In this instance, digital intervention clearly improved student attention, however the ‘depth’ of their learning remained unclear and requires further research.

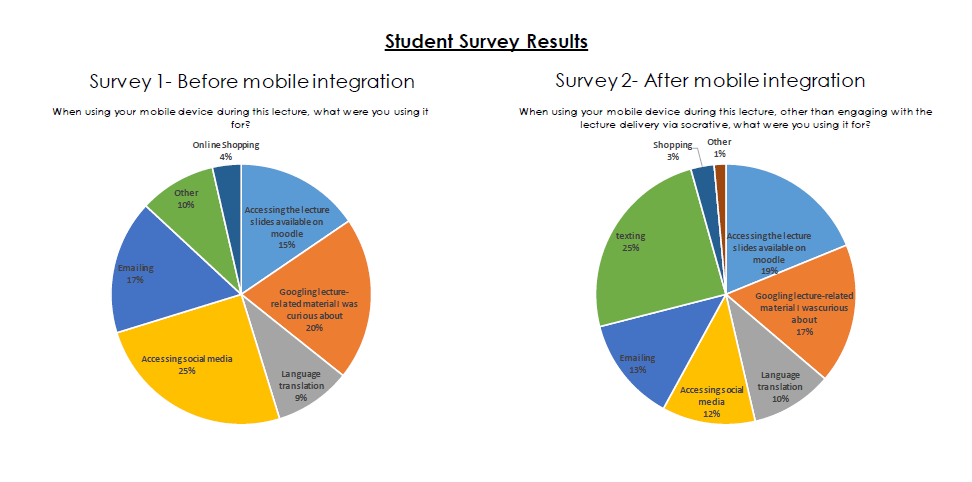

Based upon these results, depicting student concentration levels, we realised that it was important to determine what exactly the students were using their phones for (if they were not using them to integrate with the lecture). Data indicated that there was a definite shift in the content that students were viewing, switching from user-led browsing before mobile integration (such as social media and online shopping) to more response-led content after (for example replying to messages via text and email). In fact, the use of ‘browsing’ across both social media and online shopping almost halved in the ‘digital’ lecture, from 29% collectively to only 15% after mobile integration (Figure 4). This would further support the points made by the student focus group who stated that incoming communication ‘can’t wait’ and they felt a ‘need to respond’. This also made it clear that although integrating mobile phones into the lecture would not necessarily reduce the amount students were looking at their phones for non-lecture related material, it may be possible to navigate the cohort away from a more passive (and therefore disinterested) approach, towards a more interactive learning experience (Khan, 2012).

It is also useful to consider which parts of the lectures students found most engaging, both before and after mobile phones had been fully integrated into the lesson plan. It was critical to ensure the lectures incorporated not only mobile phones, but also other more traditional engagement tasks. Following the work of Bligh (1998), Hayes et al. (2012) or Biggs and Tang (2011) – the building of both the lectures involved planning strategic blocks of time where methods such as ‘buzz groups’, flip chart integration and video clips were used to fully engage and ‘arouse’ the cohort’s attention. Interestingly, despite students’ views that traditional means are the most engaging, collectively the use of flip charts, video clips and discussion reduced from 68% to 15%, even though the lecturer’s style and delivery remained consistent. In the ‘digital’ lecture the mobile device seemed to replace traditional methods. As Bligh outlines, even though integrating mobile devices is clearly an attractive prospect for the student, the best route to creating interesting and therefore engaging classes is that the lecturers themselves display interest and enthusiasm (1998).

In the surveys taken before and after mobile integration, students expressed very different views. This could be due to a lack of experience on their part, as mobile phones are not normally used in lectures, meaning it is difficult to clearly reference what ‘integration’ of mobiles means for the lesson plan and their learning. Prior to mobile integration, over a third of the cohort felt that being able to use their mobile as an integrated part of the lesson would improve their concentration and learning, compared to 94% after the lecture that used Socrative. This statistic reveals the use of mobiles in lectures to be a positive learning experience, further demonstrating what Bligh describes as a ‘desire for interaction’ amongst the student population (1998, p.67). Once aware of the technology available via mobile phones, it seemed that students were fully engaged with the format and felt it to be of benefit.

The concept of bringing a device to a lecture and using it to engage with content is a relatively recent idea within industry as well as in the teaching, with some views that it not only increases participation, but also enables learning to be self-directed. Following research undertaken and reviewing the unit evaluation report, it became clear that as Hardison has termed it (2013), a ‘Bring Your Own Device’ or ‘BYOD’ initiative, was a positive experience that allowed students to interact with the subject, and tutors seem also to benefit in terms of engagement (Elearning Industry, 2016). As indicated by their feedback, students valued the opportunity to not only collaborate but also to use ‘shared cloud spaces’ in working with other students, in classroom discussions and in researching content. Students requested more interactive methods (including Socrative) and described their learning experience as ‘fascinating and engaging’. In addition, they appeared very aware of increasing phone culture, outlining that the methods used responded to the need for ‘connected learning’ in this environment (ISTE, 2014). The use of technology, but also the way in which teaching methods were ‘mixed up’ was highlighted as a positive strength of the digital lecture, demonstrating how a combination of traditional and digital methods were the most effective way to an engaged cohort.

Industry insight into professional practice was gathered via 2 interviews, in order to evaluate the scope in terms of BYOD and evaluate it as a means of preparing students for employment. Once again, interviewees revealed that the mobile phone was perceived as a distraction, in a similar fashion to academics, highlighting that devices cause employees to lose focus in critical scenarios and meetings. Both of the industry interviews conducted, outlined that mobiles had on occasion been banned from meetings, however this ban was viewed as both positive and negative in terms of its value. Mobile phones in industry, were revealed to be critical for keeping up to date with communication – through emails and telephone calls – as well as for managing time through diaries and planners. Once again, information being too readily accessible was an issue, with devices once again being perceived as ‘difficult to get away from’. Though there was limited to no use of mobile phones within company meetings, they were present in various other guises. Conferences seemed to have adapted mobile phones as an engagement tool, in some cases making itineraries available only via an app, instead of printed media and handouts. Mobiles were stated as being integrated further at conference level – with audiences able to send questions to key speakers via a Twitter feed and so forth. As also raised by Honore and Schofield (2009), those interviewed were of the impression that technologies like this could potentially impact on behaviour and that, whilst they enabled more delegates to engage, there could potentially be a lack of personal integration.

According to these interviews, mobile phones were being used in industry not only to communicate via email and telephone calls but also via platforms such as WeChat, as such platforms allowed for instantaneous replies, rendering emailing in such situations ‘pointless’. With such integrated use of mobile phones and as they become more vital to professional practice, it is therefore critical to not only integrate them into academic environments, but also to encourage discipline and structure when using mobile devices and ensure students are appraised of etiquette and appropriate usage when embarking on a professional career.

Reviewing this research, there were two clear and different threads to the investigation. The first involves student engagement and the second relates to the optimum structure adopted within a lecture. When teaching what Levy describes as the ‘distracted generation’ (2014) of today, it is critical to keep pace with the way in which they embrace technology and ensure that teaching methods not only integrate mobile phone technology (in order to deliver an engaging learning experience), but also that it is delivered in a structured and clear fashion. As addressed by this research project, mobile phones should ‘not be ignored’ (Beland and Murphy, 2016, p.17). Instead they should be harnessed to improve engagement and encourage more meaningful learning.

This project raises questions about teaching style and delivery. Students demonstrated better engagement through the integration of mobile phones into lecture delivery, yet it is not this method alone that will deliver a learning experience at once revolutionary and that inspires deep learning on individual levels. Whilst undoubtedly integrating the mobile phone at strategic points could increase student engagement, it is clear that the structure and delivery style of the individual lecturer remains critical. How students view and use mobiles in academia, but also how educators manage this, raises difficult questions about discipline and how such activities can be managed. Often students seem ‘addicted’ to their phones (Barret, 2012), and educators may in fact be encouraging this dependency in ways that will have a negative impact upon their professional careers, where they may be required to restrict and monitor their behaviours in this regard. In managing this challenging behaviour, staff must integrate the devices in a productive fashion.

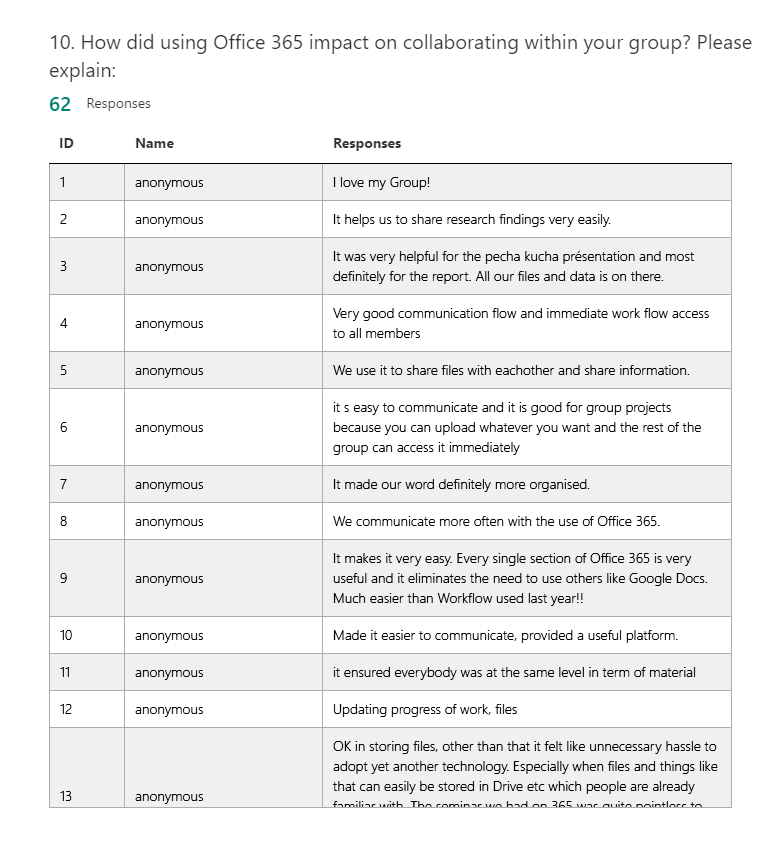

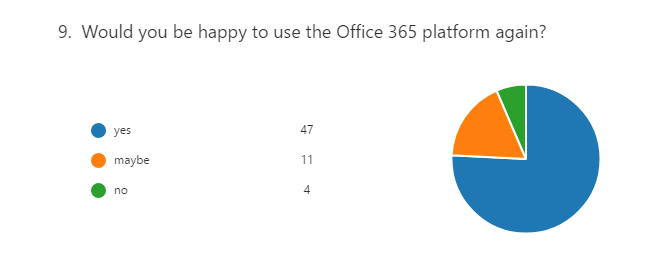

Following in-class conversations with students, further research is required into digital platforms such as ‘Google sheets’ and ‘Padlet’, as well as the use of other mainstream social media such as Twitter and Facebook. As a result of this research, a unit is currently integrating the Microsoft platform Office 365 with positive results to date (Figure 5). This platform enables students to collaborate online in a virtual space, and teaching staff to remotely manage engagement (in class and outside of lesson time). It was chosen as all students and staff have access to it via University IT subscriptions, due to its ease of access (via an app) and its flexibility. Students are keen to use the platform again (Figure 6).

Tech-literacy is an important area of research that is being addressed within the Fashion Business School, with time allocated to share findings and discuss the ways in which some of the strategies used during this research project can be adopted more widely. Mobile devices need to be viewed as useful teaching tools, rather than distractions. They should be integrated alongside more traditional teaching methods, for a fully immersive and engaging learning experience. Implemented correctly the tools available via these devices can enhance student learning. Using mobile devices, within the lesson and as part of the teaching plan acts as a way of better engaging students, but also as preparation for professional futures. Teaching staff need to ensure students are made aware of the appropriateness of using their mobile devices, making them aware of their possible disruption to productivity and therefore enabling them to fully understand how to manage usage within a professional work place environment.

Bailey, C. (2015) Christopher Bailey introduces Burberry 121 Regent Street, London. Available at: https://youtu.be/s955GeCtRsY (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Barret, V. (2012) 'A new label for kids today: the distracted generation', Forbes Magazine: Tech, 1 November. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/victoriabarret/2012/11/01/a-new-label-for-kids-today-the-distracted-generation/#5ee084e258ec (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Baturay, M.H. and Bay, O.F. (2010) ‘The effects of problem-based learning on the classroom community perceptions and achievement of web-based education students’, Computers and Education, 55(1), pp. 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.12.001.

Beland, L.P. and Murphy, R. (2016) ‘Ill communication: technology, distraction and student performance’, Labour Economics, 41, pp.61–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.04.004.

Biggs, J. and Tang, C. (2011) Teaching for quality learning at university. 4th edn. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Bligh, D.A. (1998) What’s the use of Lectures?. 5th edn. Bristol: Intellect.

Briggs, S. (2014) ‘The science of attention: how to capture and hold the attention of easily distracted students’, InformED, 28 June. Available at: http://www.opencolleges.edu.au/informed/features/30-tricks-for-capturing-students-attention/ (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Childalert (2017) ‘Mobile phones: the effects on children’, childalert. Available at: http://www.childalert.co.uk/article.php?articles_id=429 (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Cleaver, E., Lintern, M. and McLinden, M. (2014) Teaching and learning in Higher Education: disciplinary approaches to educational enquiry. London: Sage Publications.

Gerson, D. (2015) ‘What to do about texting in class, according to 11 teachers’, LA Times, 4 November. Available at: http://www.latimes.com/local/education/la-me-how-teachers-cope-with-texting-in-class-20151103-htmlstory (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Hardison, J. (2013) ‘Part 1: 44 smart ways to use smartphones in class’, Getting Smart, 7 January. Available at: http://www.gettingsmart.com/2013/01/part-1-44-smart-ways-to-use-smartphones-in-class/ (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Hayes, A., Hayes, K., Habeshaw, S., Gibbs, G. and Habeshaw, T. (2012) 53 interesting things to do in your lectures: tips and strategies for really effective lectures and presentations. Ely: Professional and Higher Partnership Ltd.

Herlong, T. (2015) ‘Cell phones in the classroom, to fight it or embrace it’, WBTW News13, 11 September. Available at: http://wbtw.com/2015/09/09/cell-phones-in-the-classroom-to-fight-it-or-embrace-it/ (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Honore, S. and Schofield, C.B. (2009) Generation Y: inside out. A multi-generational view of Generation Y - learning and working. Ashridge: Ashridge Executive Education, HULT. Available at: https://www.ashridge.org.uk/Media-Library/Ashridge/PDFs/Publications/GenerationYInsideOut.pdf (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

International Society for Technology in Education, ISTE (2014) ISTE 2014 annual report. Available at: http://www.iste.org/about/iste-story/annual-report/2014-annual-report (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Khan, S. (2012) ‘Why long lectures are ineffective’, Time Magazine, 2 October. Available at: http://ideas.time.com/2012/10/02/why-lectures-are-ineffective (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Levy, L. (2014) ‘7 ways to deal with digital distractions in class’, Edudemic: connecting education and technology, 19 November. Available at: http://www.edudemic.com/7-ways-deal-digital-distractions/ (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Mastery Connect. (2017) Socrative. Available at: https://www.socrative.com/ (Accessed: 16 July 2017).

Purcell, K., Rainie, L. Heaps, A., Buchanan, J., Friedrich, L., Jacklin, A., Chen, C. and Zickuhr, K. (2012) How teens do research in the digital world. Washington D.C.: Pew Research Centre. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/11/01/how-teens-do-research-in-the-digital-world/ (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Rideout, V.J., Foehr, U.G. and Roberts, D.F. (2010) Generation M2: media in the lives of 8- to 18- year olds. Menlo Park, Calif.: Kaiser Family Foundation. Available at: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/8010.pdf (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Weimer, M. (ed.) (2009) Building student engagement: 15 strategies for the college classroom. Faculty Focus / Magna Publications. Available at: http://www.facultyfocus.com/free-reports/building-student-engagement-15-strategies-for-the-college-classroom/ (Accessed:19 June 2017).

University of Haifa (2012) ‘94% of high school students using cell phones in class’. Available at: http://www.newswise.com/articles/94-of-high-school-students-used-phones-during-class (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Zoe Hinton is a Lecturer on MSc International Fashion Management in the Fashion Business School at London College of Fashion.